south africa’s human spirit

an oral memoir of the truth and reconciliation commission

Re Seke Ralebala |

|

main page

production scripts

bones of memory

slices of life

worlds of licence

(2 discs)

portraits of truth

windows of history

credits

links

Good evening ladies and gentlemen, comrades, friends. I’ve called my speech tonight re seke ralebala – we should not forget. We are gathered here today to celebrate the launch of an oral memoir testifying to the indomitable spirit of South Africa’s people. This memoir, contained in a collection of six CDs, has been produced by a remarkable woman, a bundle of energy, Angie Kapelianis, assisted in the main by Darren Taylor. These two people, together with Antjie Samuel, became part of the travelling family of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. This CD collection represents one of the richest compilations of oral history in the world. It reflects our sorrow, our anguish, our relief in finding a voice to express ourselves as we struggled as South Africans to find our humanity again. The anguish of Nomonde Calata as she tells her story at the East London hearing and the solidarity of the audience when they sing Senzeni Na reminds us of how many South Africans locked their memories away until they came to the Truth Commission. When they recount their stories it is almost as if they unlock this photographic image when they testify.

Tonight I want to reflect on the struggle for humanity … what that struggle for humanity means. The journey of the Truth Commission gave us the opportunity to find ourselves. Not just victims but perpetrators too. Mandla Langa in his book Memories of Stones explores this in his character, Mpanza, the killer, who ponders on his pain and I quote:

Through all the years of wandering, of pretending to live, I have been trying to atone for Jonah’s death, exposing myself to danger, hoping to die – I still hope to die, to make sure that I never endured this moment when all is revealed.

The victim’s sister, who sees him weeping, experiences…

That what she had taken to be her own private sorrow, actually belonged to more people than she would know.

On the 15th April 1996, the first hearing of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission took place in the Eastern Cape. We are four years away from that historic event and almost 18 months have passed since the report of the Commission was handed to former President Mandela and yet the victims whom this process was meant to serve have not been told what final reparation they will receive. The silence is deafening – Ngwana ya salleng oshwela tharing!

Who are these people of whom we talk. They are those who were tortured and maimed, crippled by being shot at, mentally disturbed by the trauma they have undergone, the mothers, fathers, brothers and sisters of those who were killed. In many instances they have put to rest their hope that their loved ones are still alive and still they wait for acknowledgement of their pain. Zahrah Narkedien in her testimony at the prison hearing cries…

A part of my soul was eaten up by maggots and I will never recover it again.

When our country accepted that we would go the Truth Commission route, we accepted that we would pursue a model of restorative justice rather than retributive justice. Cynthia Ngewu, the mother of one of the Guguletu Seven, expressed her vision of this concept:

This thing called reconciliation … if I am understanding it correctly … if it means this perpetrator, this man who has killed Christopher Piet, if it means he becomes human again, this man, so that I, so that all of us can get our humanity back … then I agree, then I support it all.

But this notion of restorative justice is in trouble. It is jeopardised by our failure to make changes in the material circumstances of those who came forward to tell their stories and whom we refer to as victims but who are in fact survivors of not just apartheid but of the pain of the Truth Commission process as well. Our reparation policy proposes specific symbolic economic reparation for individual victims as well as steps which will contribute to healing, such as providing gravestones, reparations in the form of monuments, heroes’ acres, bursaries for victims and their children, and support of a medical and social welfare nature. It deals with long-term institutional measures such as treatment for trauma and post-traumatic stress so that our people can heal. Our recommendations were designed to create a more accountable and caring society with a vision of economic and social transformation.

But I fear that if we do not deal with this vision and this promise we made to our people, then we may also experience what is happening in Zimbabwe. In the twenty years that went by, no effort was made by that government to deal with war veterans and now that unfinished business may destroy the present. In Chile, General Pinochet must have thought that his future was secured with the amnesty he gave himself, little dreaming that a Spanish magistrate, Garcia, would use a legal doctrine to turn that around. And whilst General Pinochet may have been allowed to return to Chile, the people of Chile have been re-galvanised into action and already 80 new charges have been added to the indictment that is being prepared for him at home. Chileans are calling out for justice and this time around General Pinochet may not escape his destiny.

Similarly in South Africa, we hear whisperings which are becoming louder and louder from victims that they too have a case. That our Constitutional Court in fact established that amnesty was only possible because of the commitment to reparations, which the court expressed as being even more encompassing than compensation. Already victims indicate that because of their perceived betrayal, that they are considering a class action for reparations. Victims’ groups have indicated that they may go to court to set aside the grant of amnesty on the basis that reparation has not been dealt with. It would be a tragedy if this fragile peace we experience is placed in turmoil because the bridge that amnesty was meant to be is broken because those who made the ultimate sacrifice have not received what they are entitled to.

Media reports express the view that there’s no money to go around yet money has been found for arms. What is the new democracy’s priorities? Another popular refrain is that people did not do this for money? This is true. Nobody did it for money. At the same time, those who participated in the struggle received a special pension, many are gainfully employed and I have not heard anybody say that they are refusing to take a salary. So why do we expect those who do not have the same access or the same opportunities that we do to make the ultimate sacrifice again? I have not seen that those who’ve been granted amnesty have lost anything other than their public image. They still have their pensions, their land, their houses, their cars, their families. And yet those whom they took away from have nothing. Sikhumbuzo, the son of Siphiwo Mtimkulu, has no father. The Trust Feed community when meeting with Brian Mitchell expressed the view that:

It is not enough for us to hear about forgiveness, would it not be wonderful if the perpetrators did something for this community.

We have seen in this century extraordinarily creative ways of dealing with our past. We are reminded again that those who forget the past are doomed to repeat it. Holocaust victims all over the world are being … invited to file claims against banks and insurance companies in Europe. In London recently stolen artworks were identified as belonging to Jewish families and discussions are underway to have those artworks returned. Dictators who travel know that they may be indicted in other countries they travel to because of the Doctrine of Universality. And many countries in the world have agreed to the setting up of an international court. If we in South Africa do not attend to fulfilling the needs of victims, then we should not be surprised if they seek those very solutions that the setting up of the Truth commission sought to avoid.

Already the old players in the past conflict have new roles. The security man of yesteryear is the private security firm of the present South Africa. The militarised youth who was fighting apartheid now finds himself on the other side. How do we avoid this? We need to ensure that reparation is made and that a program of rehabilitation is embarked on which fu … focuses mainly on youth as they represent more than 60 per cent of our population – as they hold the future of this country in their hands.

In 1988 in America, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 provided an apology by the American Government to Japanese-Americans for their internment during the Second World War, as well as $1.2 billion so that each surviving individual could receive $20 000-00. Martha Minow in her book stated that many criticise this remedy as being bittersweet and the dollar amount inadequate. However the philosopher, Jeremy Walgreen, comments and I quote:

The point of these payments was not to make up for the loss of home, business, opportunity, and standing in the community which these people suffered at the hands of their fellow citizens, nor was it to make up for the discomfort and degradation of their internment. If that were the aim, much more would be necessary. Instead, the explicit aim and actual effect of the reparations law, illustrate the symbolic significance of official acknowledgement of wrongdoing, paying respect to living survivors and to a community of memory.

All of us need to become activists for reparation so that we too can pay respect to living survivors and ensure that we remember those who died who made the new South Africa a reality.

I would like us today to remember in particular those who were alive when our process began – Chris … Ribeiro, Mr [Sinqokwana] Malgas – one of the first witnesses in East London, Mr [Mahlomola Isaac] Tlale from Alexander, Hilda Phahle and many others for whom it is already too late.

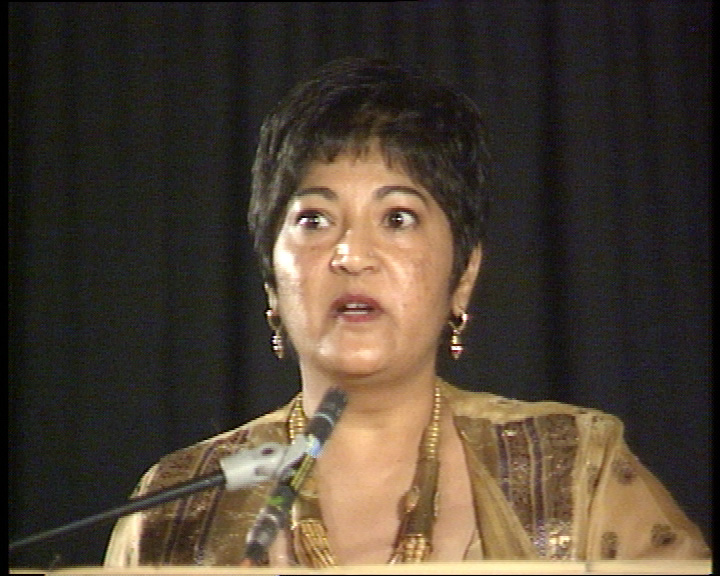

The memoirs [south africa’s human spirit – an oral memoir of the truth and reconciliation commission] constitute a living memory and I think we need to salute those who made it – Angie [Kapelianis] and her team. Thank you.Yasmin Sooka

Truth Commissioner

13 April 2000

These scripts - © SABC 2000. No unauthorised use, copying, adaptation or reproduction permitted without prior written consent of the SABC.